A “Seedy” Exploration of the 1893 Colombian Exposition

- Author

- Sam Wilson, Collections Intern

- Date

- December 19, 2025

Throughout my time as a collections intern at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum I worked on a variety of different projects, but none brought me as much personal satisfaction as my work identifying and cataloguing one specific collection of seeds. Over the course of my fall semester, I worked closely with almost 100 vials of seeds acquired from the Field Museum in the 1950s. While I originally thought I would just be counting, cleaning, and rehousing old seeds, the project became much more. The process laid out seemed simple at the beginning: moving groups of seeds from dirty old vials to clean and standardized containers, and then transcribing their information into the museum’s online collections management system, Arctos. During what could have been a tedious transcription process, I encountered a mystery, and ended up falling down a hole of late-night research leading me back to 1893.

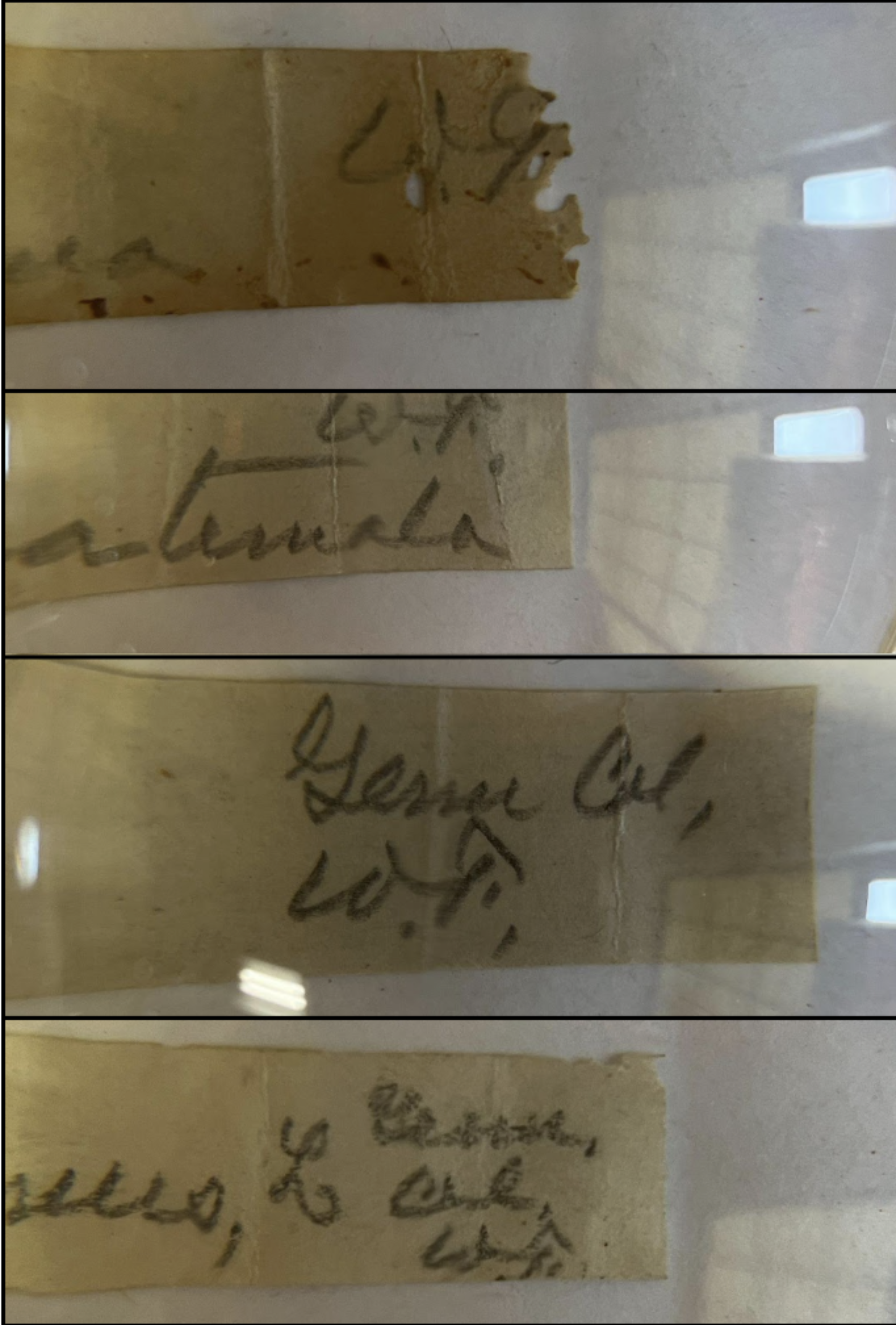

Although many of the seeds had limited information beyond just their scientific names, we knew that they could have been collected as early as the 1800s. Because of their age, the cursive script was often faded or hard to decipher, especially due to my lack of experience with cursive handwriting. While some labels were easier to read than others, there were repeated acronyms and phrases I couldn’t resolve. Were they a clue about the specimen’s location, the initials of the collector, or some sort of taxonomic shorthand? These two little letters, “W.F.”, wouldn’t leave me alone, popping up on different labels with the same repeated phrases. Time and again, my internet searches came up short.

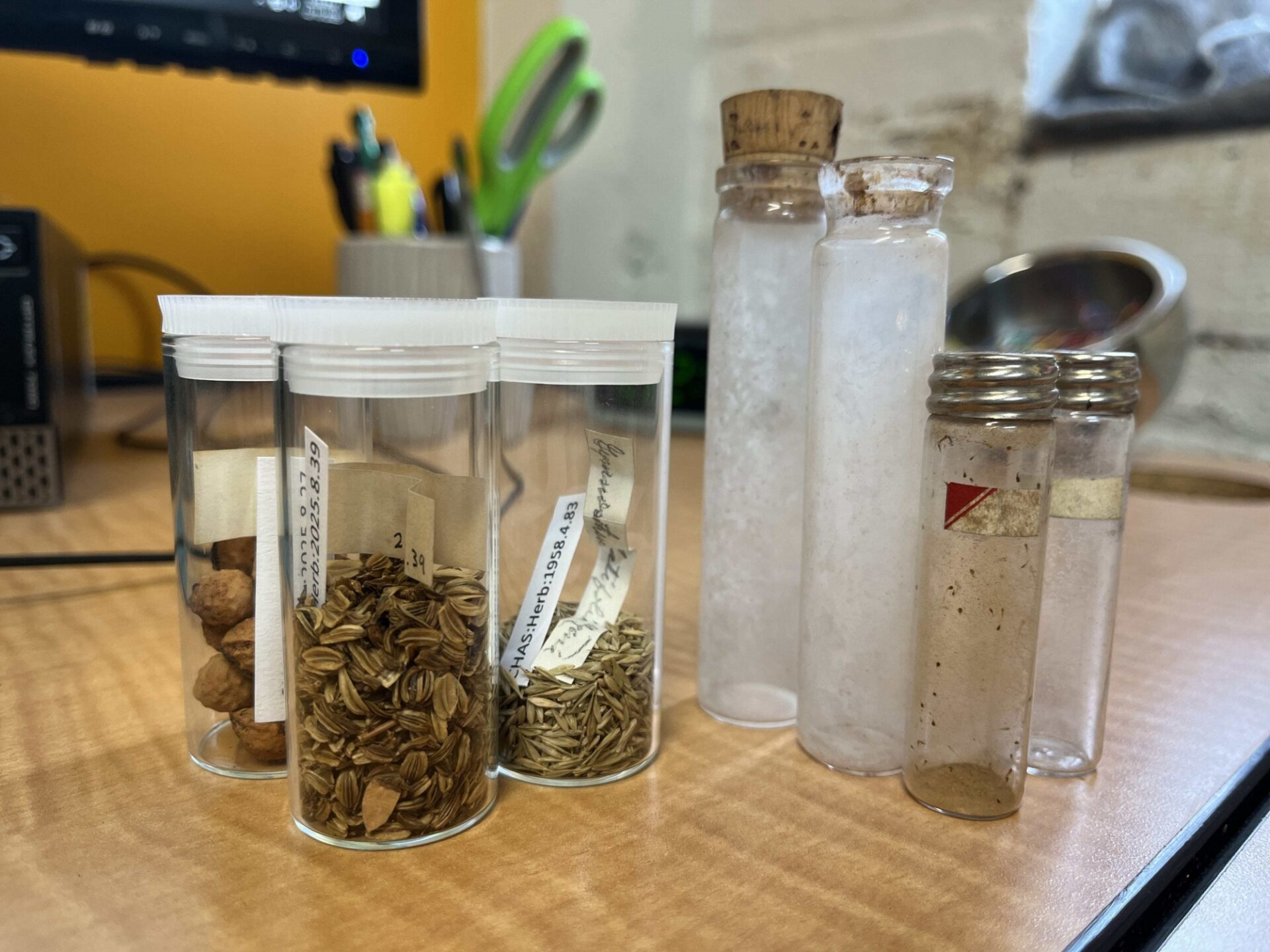

Comparison of the original vials and the containers that now house the specimens

Images of the original labels of four different specimens, all showing some variation of “W.F.” or “Germ. Col, W.F.”

After staring at these labels for what felt like weeks, I felt stuck, not even sure if I was interpreting the handwriting correctly. As my cursive skills improved throughout the semester, I could determine that these labels said “Germ. Col.”, but this was once again a dead end. Deciding to move past what was vexing me, I turned my attention to some of the less well-preserved specimens, spending days cleaning out carcasses and frass (dust-like droppings of insect larvae) that were left behind by dermestid beetles feeding on the seeds. I dedicated all of my available efforts to the time-consuming process of cleaning these vials one by one, but was never able to forget the road-blocks awaiting me once I was finished. Although this change of focus was originally a method of procrastination, it ended up as the key to unlocking my looming mystery.

“Germ Coll, World Fair”

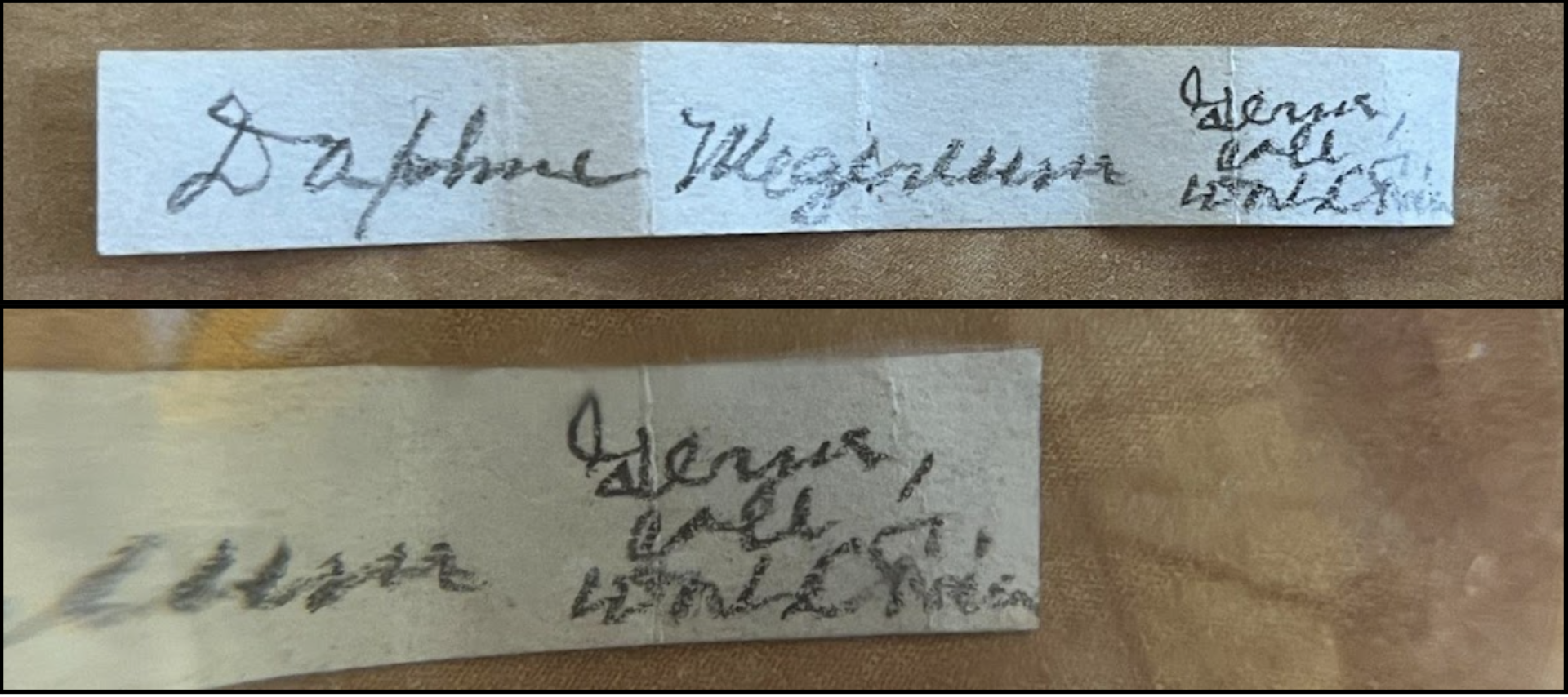

Images of the label of Daphne mezereum, with the description “Germ Coll, World Fair"

While I was transcribing and integrating the seeds I had just finished cleaning, one label stuck out to me, and these four short words became my saving grace. I quickly narrowed my search, looking through information about the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, and discovered there were indeed collections focused on the germination of different plants and the preservation of their seeds. This confirmation was the proudest moment of all my time with the Museum. I had finally cracked the code that had been hanging over me for months, and was able to finish the project that had become my sole focus.

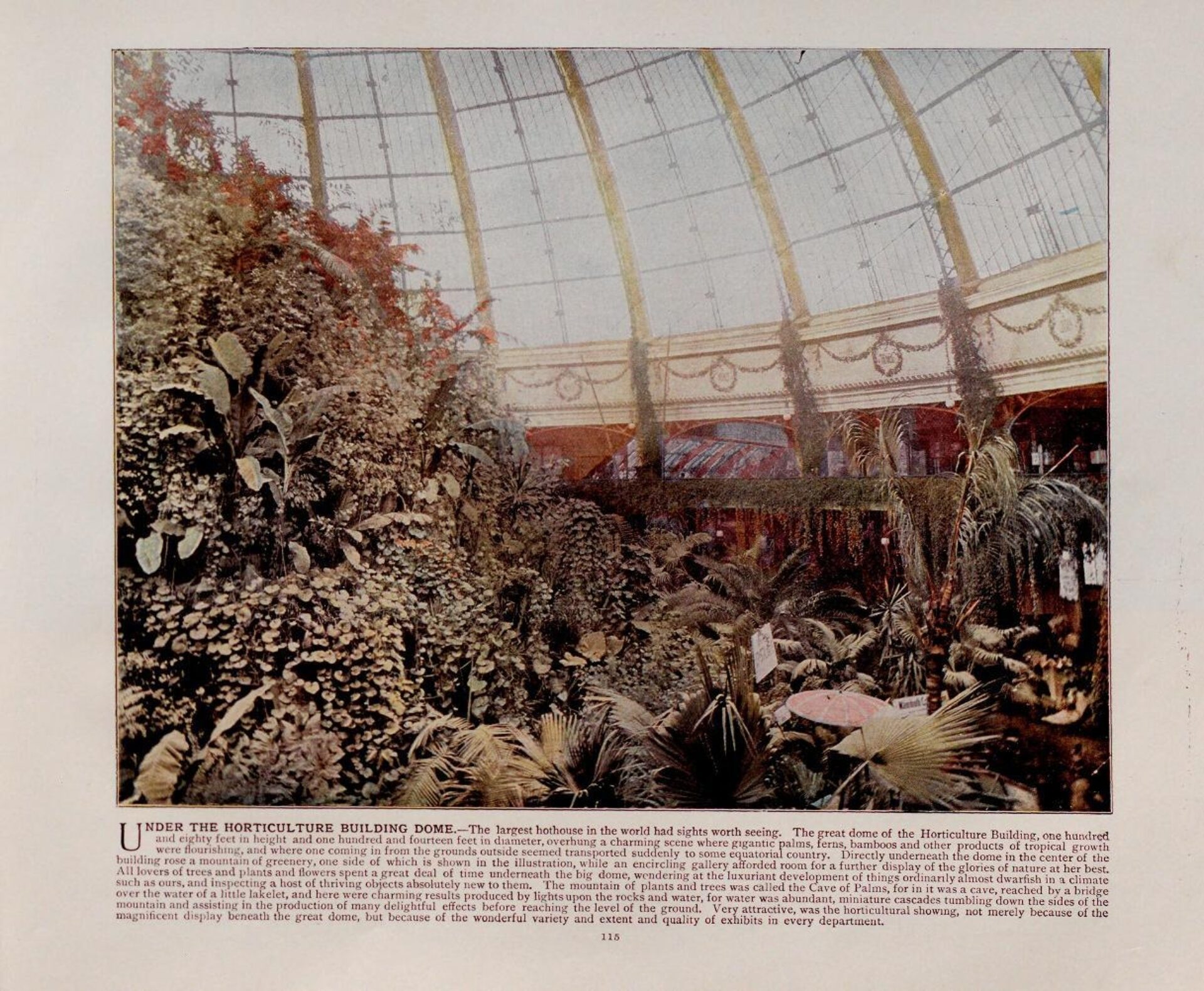

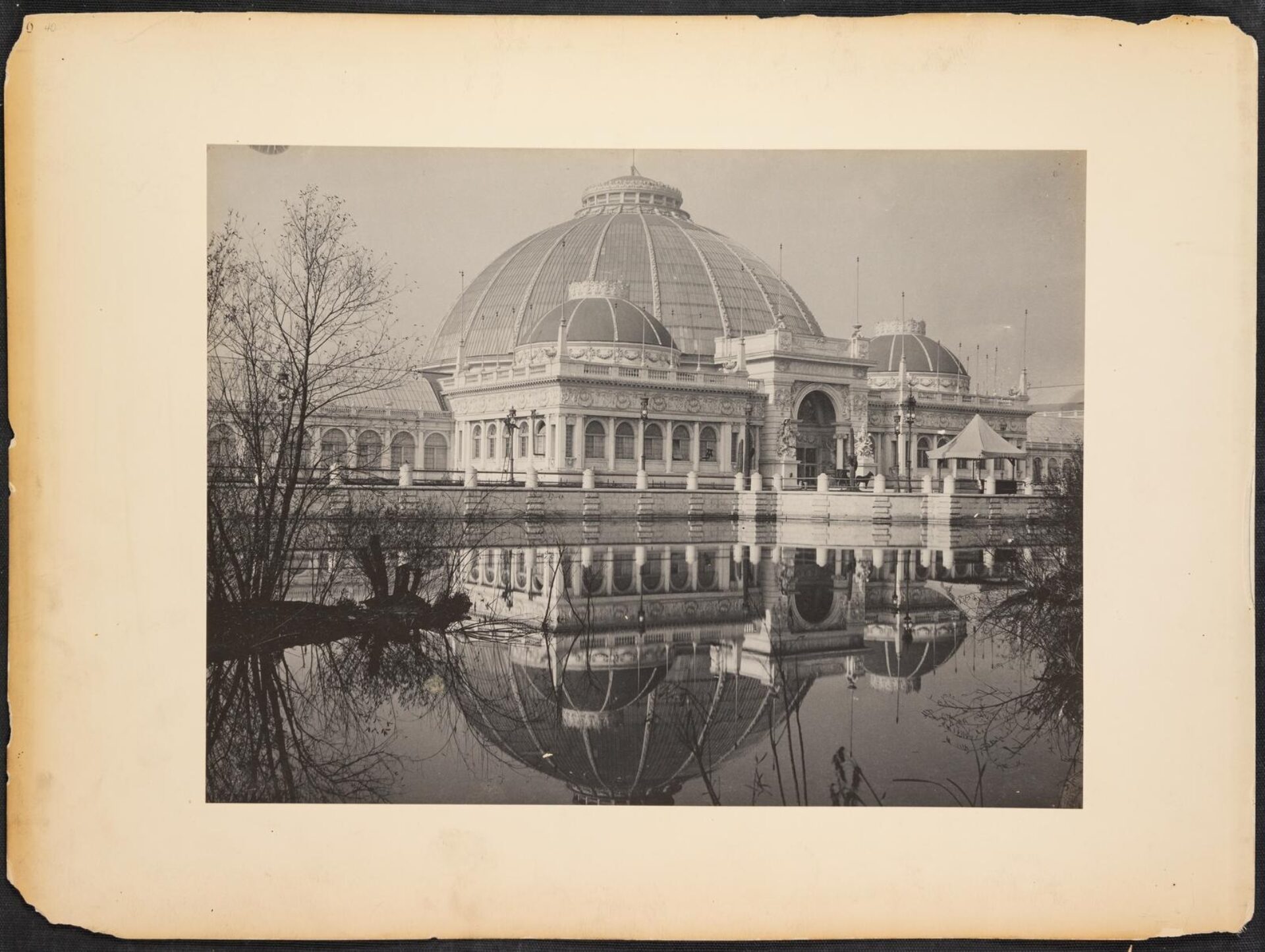

Once the project was finished, my curiosity about these seeds lingered, leading me to do more research during my own time into the 1893 Colombian Exposition and its botanical exhibits. While there is no documentation of an explicit “germination collection”, there were exhibits solely dedicated to the showing of different seeds, with greenhouses near the main botanical building focused on the propagation and forcing (prompting plant growth outside of the natural growing season) of different plant species. There were also multiple occurrences of seeds being used in the decor of the Horticultural Building: on display in jars and used as detailing for sculptures and panels. During my search for information about this seed collection, I looked through any writing about the Fair’s horticultural exhibit that I could find, gaining an appreciation for an aspect of Chicago’s history that I had never thought about before.

Image of the central horticultural exhibit from Picturesque World’s Fair, An Elaborate Collection of Colored Views—Published with the Endorsement and Approval of George R. Davis, 1894

Image of one of the greenhouse buildings from the Horticultural Exhibit (Getty Museum Collection)

Image of the Horticultural Building Exterior (Chicago Public Library. Special Collections & Preservation Division)

Image of the Horticultural Building Exterior (Chicago Public Library. Special Collections & Preservation Division)

At the time of the Fair, the exhibit was the most comprehensive and ambitious showing of botany in the world, with plants provided by every existing state in the U.S., as well as nations from around the globe. When looking into the seeds I had identified online, I found that many of the species associated were not even native to the United States, with very few of them having a single occurrence in the states prior to the World’s Fair in the 1890s. This made me wonder where in the world these seeds came from, and how they made their way to Chicago almost 150 years ago.

Occurrence of Abelmoschus moschatus (Annual Hibiscus) recorded from 1840 to 1900 (screenshot from GBIF)

The lack of documentation associated with many historical specimens is a real challenge for archival collections, like those at the Chicago Academy of Sciences and its Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum. Many types of specimens–not just seeds–are riddled with lacking information, but it doesn’t make them any less valuable, and the research process is important no matter where you start. Although these seeds had very minimal data, by following the few breadcrumbs I was given, I was able to learn more about the path they may have followed, and how they fit into a larger historical context. We should remember not to overlook the archival underdogs, because the smallest of seeds can lead to the most rewarding discoveries.

Some mysteries can never be solved, I don’t think we will ever know where these seeds truly came from, but I will always appreciate the research journey they took me on. Having never properly looked into the World’s Fair before, I was amazed by the ambitious scale of the event, and how much dedicated work it took. What started with frustration over faint cursive scripts ended with reading handwritten diary entries and newspapers from the 19th century. Whether it was exhibit reviews, breaking news, or someone's daily schedule, I am grateful to have seen first hand accounts of an event that defined Chicago’s history, and brought together the scientists and citizens of 1893.

Sources

Abelmoschus moschatus (L.) Medik. in GBIF Secretariat (2023). GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. Checklist dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-12-12.

A Week at the Fair, Illustrating the Exhibits and Wonders of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Rand, McNally & Co., 1893.

Cannalore. “Chicago World’s Fair, 1893.” The Canna Chronicles, 18 Oct. 2017, www.thecannachronicles.com/chicago-worlds-fair-1893/.

Cummings, Scott. “Progress of the Century: The Celebrated Agave Plant of the 1893 World’s Fair.” Chicago’s 1893 World's Fair, 7 May 2021, worldsfairchicago1893.com/2021/05/07/progress-of-the-century-the-celebrated-agave-plant-of-the-1893-worlds-fair/.

Johnson, Rossiter. A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893, D. Appleton and Company, New York, NY, 1897.

Lemaire, Gorette. “Horticulture - Expo Chicago 1893.” Worldfairs.Info, 1 Feb. 2001, en.worldfairs.info/expopavillondetails.php?expo_id=7&pavillon_id=1567.