Smooth Greensnake Research

- Author

- Sebastien Nacher, Snake Field Conservation Technician

- Date

- November 24, 2025

Did you know that many fascinating wild snake species live within driving distance of downtown Chicago? This past summer, I encountered over 500 snakes in natural areas across the Chicagoland area as part of conservation research efforts by the Chicago Academy of Sciences, with funding from the Morris Animal Foundation’s grassland wildlife health grant. The research team I was a part of is led by Dr. Sacerdote-Velat, who is the Curator of Biology and Herpetology/Vice President of Conservation Sciences at the Chicago Academy of Sciences and has been studying wildlife in the Chicagoland region for over 20 years. As part of her team, it was my job to search natural areas for snakes, briefly capture them to collect data and samples for laboratory analyses, and safely release them back into their wild habitat.

(Important note: All handling of snakes was done under an active research permit and done in a manner that was safe and minimally stressful for the snakes, who were safely released where I found them after I collected samples and data)

Who Are Smooth Greensnakes?

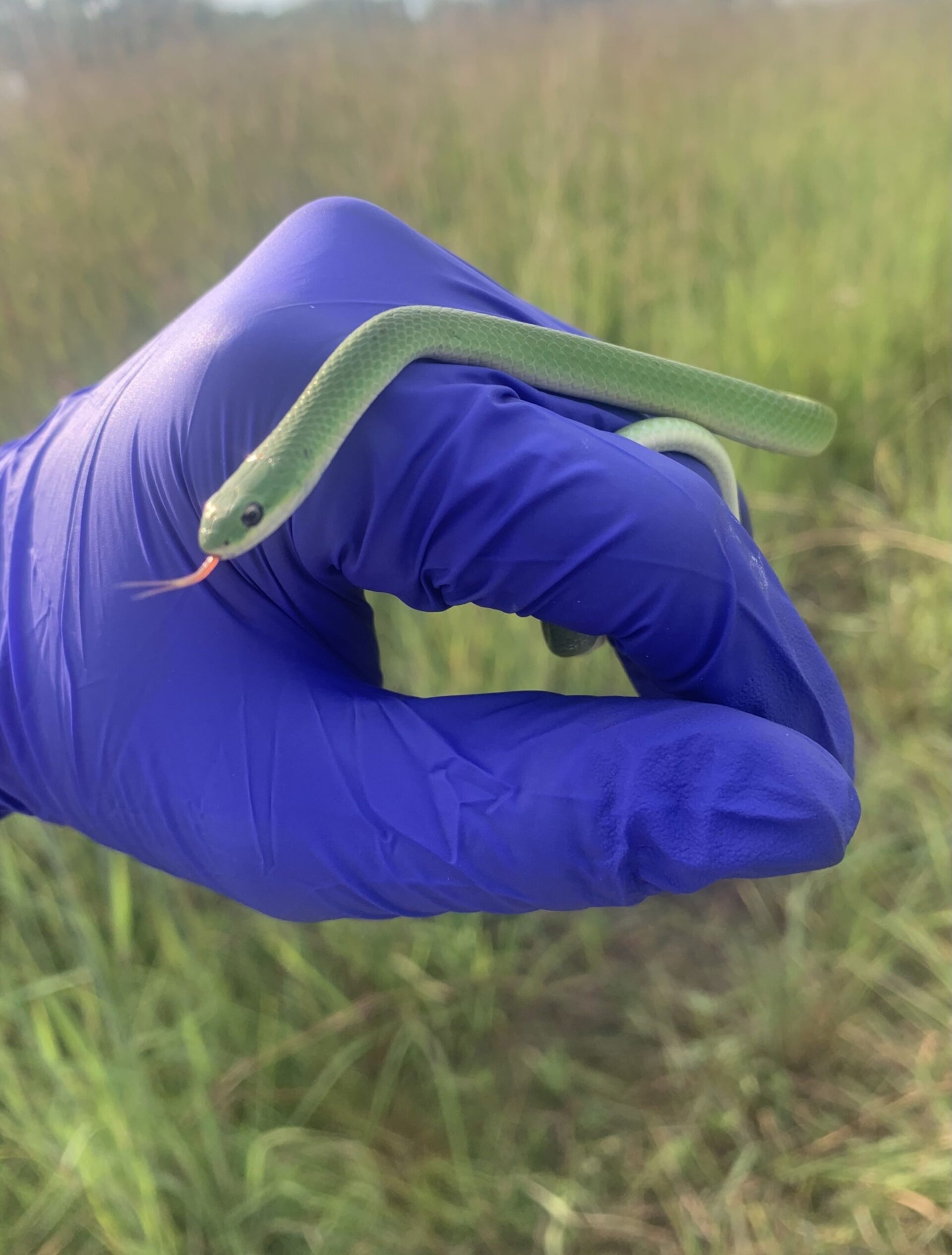

The primary study species of Dr. Sacerdote-Velat’s research is the smooth greensnake (Opheodrys vernalis). They’re a small, non-venomous species who live primarily in grassland habitats. As you may imagine from the beautiful, bright green color of their scales, they are experts in camouflage when surrounded by vegetation: a smooth greensnake slithering through grass can become invisible from one moment to the next - the same can’t be said, though, when a smooth greensnake is on gray concrete.

Smooth greensnakes eat insects and therefore have very small teeth that aren’t noticeable or harmful, and they are docile and gentle in nature. Their primary defense behavior is to flee and hide in nearby vegetation, and I never had an adult smooth greensnake get defensive and attempt to bite me when handling them. Similarly, hatchling smooth greensnakes will attempt to flee but otherwise use their signature defense behavior of opening their mouths and lifting the front half of their bodies like a cobra, which is thought to intimidate potential predators such as birds. They don’t strike or bite; they just make themselves look threatening. This behavior might be scary to us humans as well if the babies weren’t about the size of a worm; instead, this behavior makes the babies even more adorable and sometimes makes it look like they are smiling at you!

If you want to learn more about smooth greensnakes and their conservation (and other Chicagoland wildlife such as frogs and turtles), check out these episodes of the Primal Biology Show!

What Are Some Environmental Threats to Smooth Greensnakes?

Smooth greensnakes are currently listed as a species of Greatest Conservation Need in Illinois. Due to declining populations, they are in consideration for being listed as an Endangered and Threatened species in Illinois.

Two important reasons we know have caused declines of smooth greensnake populations (and other wildlife species as well) are loss of habitat and habitat fragmentation, which is when what used to be one big habitat is broken up into many small, disconnected habitats (e.g. the Chicagoland region used to be one big natural habitat; now, natural areas are a fraction of the size and separated by urban, industrial, and agricultural developments). Two other lesser researched reasons for smooth greensnake population declines are first that they are being affected by a disease called snake fungal disease and second that they may also potentially be absorbing toxins from heavy metal pollution in the soil.

Smooth greensnakes are a sensitive species, and sensitive species in general are great indicators of ecosystem health: these species often have particular needs and therefore are the first to show signs of negative environmental changes. So while Dr. Sacerdote-Velat’s research focuses on the health of smooth greensnakes themselves, it allows us to learn about the health of their habitats as well.

How Do We Research Smooth Greensnakes?

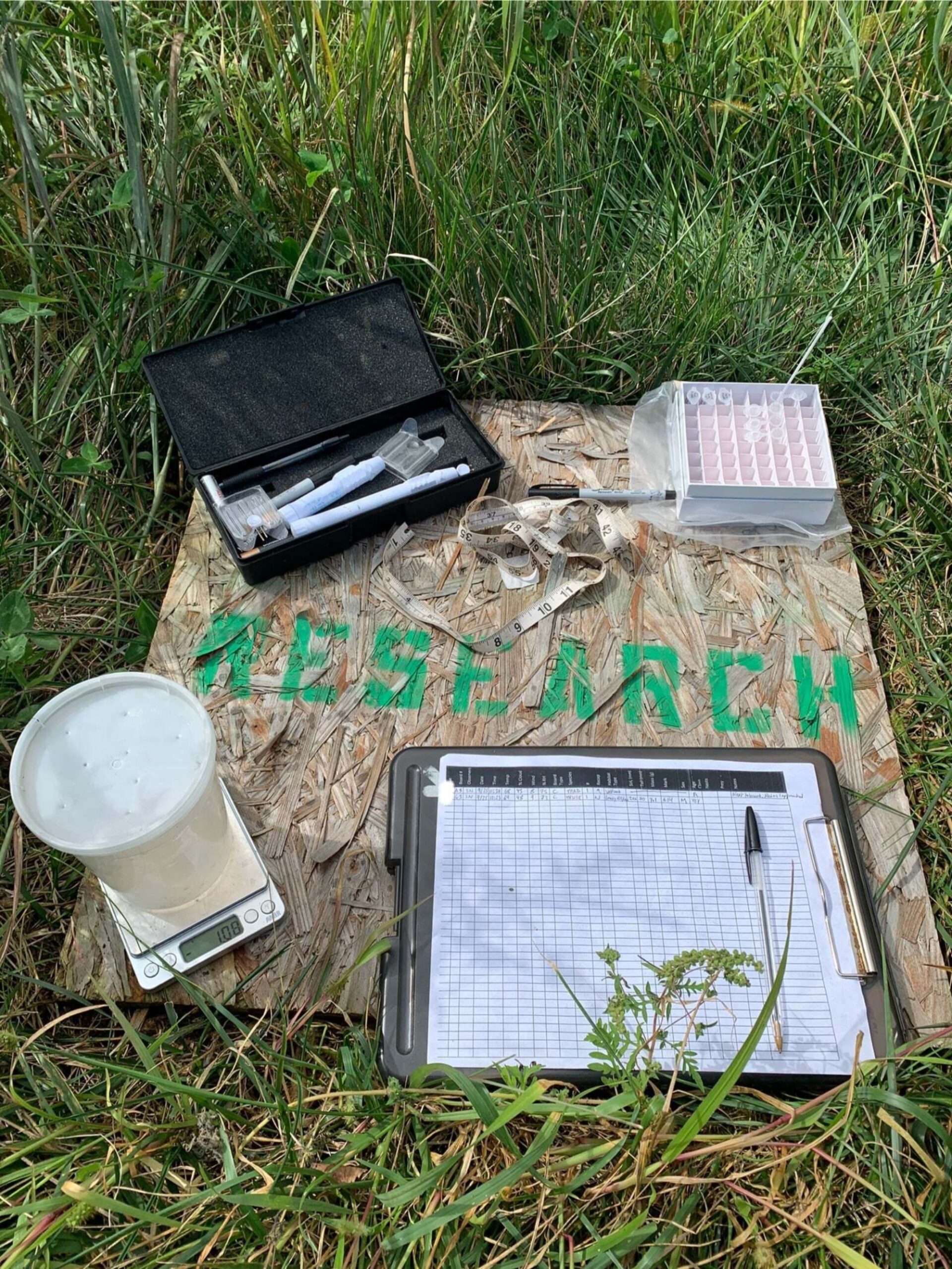

So what does this all mean for me as a snake field technician? Well, my job was to search for snakes of any species to collect some basic environmental data (temperature, humidity, and cloud cover for example), geographical data of the snakes’ locations, and morphological data on the size, age, and sex of each snake.

Even though smooth greensnakes are the focus of Dr. Sacerdote-Velat’s research, this data on other snake species is still useful to provide a glimpse into the broader ecosystems and habitats that smooth greensnakes call home. The data also helps us understand more specific things, such as whether different snake species live in the same areas as each other and whether other snake population sizes - not just smooth greensnakes - have changed over time. Besides, after some practice, data collection for snakes that aren’t smooth greensnakes only took about 6-7 minutes, so it’s a small amount of time for valuable information! For smooth greensnakes, the protocol was the same but with some additional steps to address the main research objectives.

One research objective is the surveillance of snake fungal disease (SFD) in smooth greensnake populations at different sites across the Chicagoland area. SFD affects many snake species across the eastern and midwestern United States, and symptoms can be visible on a snakes’ scales in the form of dermal lesions such as blistered, rotting, or discolored scales. In extreme cases, we’ve found smooth greensnakes who have lost an eye due to SFD symptoms on their head. Whenever I captured a smooth greensnake, regardless of whether they had obvious SFD symptoms or not, I collected non-invasive surveillance swab samples by rubbing a swab over the scales all over the snake’s body. These samples will be sent to the University of Illinois Wildlife Epidemiology Laboratory for analyses that will detect the presence of the harmful fungus species responsible for SFD. I also took photographs of smooth greensnakes and I noted the type and location of visible lesions - these will be valuable to revisit after laboratory analyses are complete to compare the appearance of scales in photographs with positive or negative SFD diagnoses.

Another research objective was to monitor smooth greensnake nests during nesting season. While most Chicagoland snake species don’t lay eggs, smooth greensnakes lay nests of eggs to incubate externally for a variable period of time before hatching. I monitored each nest’s progression over weeks of incubation and tracked each egg’s fate - if I got lucky, I would even see some of the babies hatch! Once hatched, eggshells and samples of soil in contact with the nests were collected to conduct analyses on potential heavy metal accumulation in smooth greensnakes. Based on their diet and lifestyles, smooth greensnakes may be susceptible to pollution and heavy metal toxicity, and measurements of heavy metal accumulation in their eggs and/or surrounding soil could be valuable indicators of the health of the surrounding terrestrial ecosystem. In addition to the heavy metal analysis, finding nests at a site also tells us that smooth greensnakes are present there; this may seem obvious, but smooth greensnakes can be difficult to find - at a site where I hadn’t found a single smooth greensnake in the 6 months I visited it, the presence of 32 smooth greensnake eggs told us they did indeed live there and are reproducing.

What Can We Learn From This Research?

By investigating both disease and potential toxins (a source of reduced health and potential mortality) and the rate of nesting success or failure (a potential source of population growth... or population decline if eggs aren’t surviving), we can gain insights on the decline of smooth greensnake populations to make informed decisions for their conservation! Also, as smooth greensnakes may be a good indicator species for grassland habitats, insights into their decline can give us valuable knowledge on the environmental conditions degrading their habitats, and this knowledge can guide land management efforts to conserve and restore the natural areas they call home.