Calling Frog Survey Resources

We are a community science program surveying frog populations and establishing survey routes throughout Illinois. Apply now to become a volunteer monitor!

Our goal is to establish calling frog survey routes throughout the Chicago region, resulting in amphibian abundance and distribution data. Data from the Calling Frog Survey will be used to guide regional conservation planning and local land management.

New to the Calling Frog Survey? Click here to learn more about the program!

Returning frog monitor? Before the start of each new monitoring season you'll receive a returning monitor survey. Please complete the survey to confirm if you plan to continue monitoring. This information helps us reserve your existing route and determine which sites may need new monitors. Confirming your continued participation helps us maintain up to date information across the region.

Keep reading for information on Illinois frog and toad species, monitor resources, workshop dates, and more.

Please note, we review applications at the start of the calendar year, once training sessions are scheduled for February.

2026 Training Workshops for New and Returning Monitors

New volunteers must complete a beginner workshop training. Our virtual workshops are for both beginning and experienced monitors. During these workshops, we will teach and review the calls of our 13 frog and toad species, help monitors find survey sites, and discuss the monitoring protocol. Experienced monitors are encouraged to attend, in order to learn any protocol changes, obtain data sheets, review frog calls, and share lessons learned from last year. You are only required to attend one virtual monitor training workshop to learn the protocol and frog calls.

Please note, we will not assign and confirm new routes unless monitors have first completed a training workshop. Available routes are assigned first come, first served.

Volunteer Monitor Requirements:

- Click on the Apply Now button and submit an application form.

- Attend a training before beginning to monitor.

- Receive a site assignment from the CFS (public lands / accessible sites).

- Conduct a survey during each of the three monitoring periods (Feb. 20-Mar. 25, May 10-May 30, June 20-July 10).

- Submit your data online.

- We also provide ongoing training and support from the network leaders.

Workshop I

Saturday, Jan. 31, 2026, 1PM-4PM

Workshop II

Workshop III

Workshop IV

Monitor Resources

Before the Survey

Learning

Attend a workshop to learn the frog and toad species of the area, their calls, and the monitoring procedure. Workshops are offered in most Chicago wilderness counties in February. Plan to attend a workshop each year that you monitor in order to brush up on your skills and learn of other amphibian or reptile monitoring projects that are happening.

Make a commitment to learn the frog and toad calls before the first survey. You can listen to and download the calls of the native species and listen to them on your phone or computer. If you want to listen to the calls while monitoring, please use ear buds or play the calls in the car, so that you do not encourage the real frogs to call.

Establishing a Monitoring Route

If you are a returning monitor, it is best for you to continue monitoring the same sites, or routes, as last year. Feel free to add new routes to your list if you want to do more.

For those who need to establish a new monitoring route, we will work with you after the workshops to do so. Once you attend a workshop, please fill out the program application form with a short list of sites that would be convenient to you. We will work with the landowner agencies to help with site assignment based on which sites are not currently being monitored, and sites that are of high priority for scientific or land management reasons. If you have a particular forest preserve in mind, please check with your coordinator to see if it is available and appropriate for monitoring. Please note that site availability may be limited within the city of Chicago, based on the number of sites with appropriate habitat for frogs, or based on popularity of certain preserves. We will do our best to find a site that will be convenient for you.

Frogs and toads breed in ponds, swamps, lakes, etc., with a preference for temporary or semi-permanent waters. Although a temporary water body that usually dries up in a few months may appear to be a poor choice for breeding, it may in fact be an excellent choice because of the absence of tadpole predators such as fish.

Within your monitoring route(s), we recommend that you pick five listening points, or locations, for monitoring. If your site (route) is relatively small, then adjust the number of listening points accordingly. This will require one or two hours of your time on each night you monitor. If you choose more than five locations (listening points) you may not be able to sustain the effort in the future. It is important that you choose locations that are at least 200 meters apart. If you do not have a handheld GPS unit, the best alternative is your smart phone. Apple and Droid each have a free distance meter app that you can use to determine this distance accurately. If possible, try to include several habitat types (for example, a temporary woodland pond, or a marsh, or a shallow area of a lake) on your route.

Each land agency has it own procedures for allowing us night access to the preserves. You can learn the procedures by attending the workshop within the appropriate county.

Terminology-Route vs. location: Remember that we are using the term route to describe your overall site, or your entire monitoring area. We are using the term location to describe the individual listening points within each route. You may certainly choose more than one route, but please notify your coordinator if you do.

Roadside Monitoring

In rural, mixed suburban-rural, and even some forest preserve areas it is possible to establish a route by driving down roads and spotting bodies of water, which are often less than a mile apart. The route you explore should have as little automobile traffic as possible so you have a good chance of hearing breeding calls later when you are monitoring. If you can safely park your car at or near a water body at night, you can monitor it. Pick a location (listening point) where you can listen for calls each time you monitor. That spot should be no more than 100-200 feet from the water in order to be able to hear weaker mating calls (i.e. from leopard frogs). If you must leave the roadside in order to get to the listening point, it is essential that you obtain advance permission of the landowner.

Routes in Completely Developed Areas

In completely developed urban or suburban areas it is unlikely that you will be able to establish a roadside route. Although there are scattered stormwater retention ponds, corporate estate ponds, lawn ponds decorating newer subdivisions, and ponds or lagoons in city parks, most of the appropriate water bodies will be found in the forest preserves. It is best to use maps to locate water bodies within these heavily developed areas.

Finding the GPS coordinates for each of the locations (listening points):

When you record your data, you’ll need to write down the GPS coordinates for each monitoring location. The two best ways to do this are to use a hand held GPS unit or Google Earth on your smart phone. If you do not have access to either, and need to estimate the coordinates, please use the sites mentioned below.

Note: Enter the GPS coordinates as positive numbers. Our longitude is negative, but we include the W label to designate this.

To get coordinates without a phone or GPS unit:

- Find them by moving the marker on the map on the Locations page in the data entry website.

- You may also use Google Maps

- Type in your address, or some other address that will get you to the Chicago region, in the Search Google Maps box in the top left corner. Click on the Directions arrow. A marker labeled should appear on the map.

- If your marker is in the correct spot, simply right click the marker and the GPS coordinates will appear in a a box hovering over the location. If you need to adjust your marker to the correct location, simply click and drag it to the correct spot, then right click to get your coordinates.

- Other websites such as Google Earth also can find GPS coordinates for you. Please use decimal degree format if you are offered a choice — this looks like 44.4444, for example.

Conducting the Survey

Suitable Weather Conditions

When suitable weather conditions for monitoring have arrived, time your arrival at the first location (listening point) so you can begin monitoring one half hour after sunset.

Suitable weather conditions for amphibians will generally be weather conditions deemed to be marginally suitable for humans. These include periods following a rain or periods of high humidity. Warmer days are good times for monitoring, especially in early spring. Our Facebook Group, The Calling Frog Survey, is a good way to know if the weather conditions are right, so this can be a good way to judge when to go out.

Guidelines for Suitable Monitoring Weather

Period / Minimum Air Temperature (degrees Fahrenheit)

- February 25 – April 20 / 45o

- May 10 – May 30 / 55o

- June 20 – July 10 / 65o

Note that these are guidelines. If the air temperature is a few degrees below the guidelines and the frogs appear to be actively chorusing, go ahead anyway. We have to make our decision on when to monitor on the basis of a weather forecast. However, the male amphibians may be stimulated to call on the basis of the water temperature. Once the sun has set, the air cools more rapidly than the water, and the frogs may still be responding to the heat of the afternoon. For this reason, air temperature is probably not the best indicator of calling activity. But measuring water temperature is something that can only be done upon arrival; and sometimes can’t be done at all if there is no access to the shoreline. If air temperature is not approaching the minimum suggested temperature, wait until it does, even if it is past the recommended date.

Beaufort Wind Scale

Monitoring should not be conducted when the Beaufort wind scale exceeds 3. Strong winds will affect your ability to hear the calls of frogs and toads.

Beaufort Wind Scale / Wind Speed (mph) / Description

- 0 / <1 mph / CALM: smoke rises vertically

- 1 / 1-3 mph / RELATIVELY STILL: rising smoke drifts, weather vane inactive

- 2 / 4-7 mph / MODERATELY WINDY: leaves rustle, can feel wind on face

- 3 / 8-12 mph / WINDY: leaves and twigs in constant motion, small flags extend

- 4 / 13-18 / VERY WINDY: moves small branches, raises dust and loose paper (too windy to monitor)

Other Preparations

Be sure that you are following any required access procedures. These vary from county to county. You will learn of any required procedures at the training workshops.

Bring the appropriate equipment — data sheets, rubber boots or old shoes, rain gear, camera (optional), phone (do not play calls as they may stimulate frogs to call), thermometer, pencils (more than one!), flashlight, GPS unit (optional), permit (if required in your county). If you are entering forest preserve land, a whistle (in case you and your partner become separated) and a cell phone are important aids.

Since you will be conducting these surveys in the dark, you are encouraged to bring an assistant along to share in the experience. This person can help you find the sites, document some kinds of information, and substitute for you in case of an illness.

Recording Weather Data

The CFS DATA SHEET provides blank spaces for all of the necessary data:

- At each listening point (route section), record the wind strength using the Beaufort wind scale.

- At each location, record the time and measure air temperature (if you do not have a thermometer, use a weather app on your phone).

- At each location, note the percent cloud cover and choose the appropriate sky conditions category from the table on page 2 of your data sheet.

- Note that if conditions do not change during the evening, you may use your initial wind scale, temperature, and sky conditions for your starting and ending conditions.

- Weather history within the past 48 hours (rain and temperatures — above freezing or below freezing) should also be recorded.

Recording Optional Data

Optional additional information to note at each location:

- A general evaluation of water level in the wetland at the time of the survey (if possible).

- Any major changes to the breeding site since the previous survey.

- Any major changes to the habitats adjacent to the monitoring location since the previous survey.

Listening for Calls

Listen at each station for five minutes and record the Call Index (call intensity) for each species on the data sheet. If noise from traffic or other sources interferes with listening, extend the listening period for another five minutes.

Call Index Definitions

- 1 - Individual calls can be counted; there is space between calls.

- 2 - Some calls are overlapping; but individuals are still distinguishable.

- 3 - Chorus is constant, continuous and overlapping; impossible to count individuals.

- OB - Indicate in the notes field, that a species was seen (observed), but not heard during the survey. This would be reported under “incidentals” in the database.

Difficult Species to Identify

Scientists involved with this project recommend that we report the two gray tree frog species generically as “gray tree frog” because of the known difficulty in distinguishing their calls. Volunteers must record the tree frog calls and send them to their county coordinator and/or the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum (asacerdote-velat@naturemuseum.org) for further identification. It is very important to include the air temperature (and water temperature if possible) when submitting your recording. This will help scientists determine which tree frog species you have recorded.

A number of other species are of special concern because of their rarity. If you think you have heard wood frogs, Fowler’s toad, cricket frogs, pickerel frogs, or plains leopard frogs it is strongly recommended that you record the calls and/or take a photograph and submit as outlined above. Also, email or call your county coordinator and/or the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum right away in order to give the scientists an opportunity to visit the site during breeding activity.

Any time that documentation of a species is made by photos or audio recordings, please denote under the “Comments” section of the data sheet.

After the Survey

Entering Data

The deadline for entering your data is August 31. Please do not forget to enter or send in your data – we can’t use it if we don’t have it!

Please submit your data to PollardBase. If you need assistance on how to submit your data, please click here to access the PollardBase Data Entry instructions video.

When you enter or send in your results, it is important to describe the route in a manner that will allow others to know precisely where your locations (listening points) are located and where the wetland is in relation to the location. The best way to do that is to describe your walking route and provide GPS coordinates for each location. It is very helpful to indicate landmarks, such as road intersections, streams, bends in roads, or buildings, and include their relations to the listening points.

Indicate the type of wetland; for example, is it a vernal pool (i.e. temporary pond), a pond in a wood lot, a marsh, a bog, a fen, a creek, a slough, a farm pond, a retention pond, a city park pond, etc.

We recommend that you draw a map of your entire route for your own use in getting from one stop to the next.

Very Important Final Notes

Do NOT harass, take, or move any animals while monitoring. Do not play frog call recordings while conducting the survey. It is important to disturb the area as little as possible and to be aware that taking animals from forest preserves without a permit is punishable by law.

Please report any illegal activity related to rare animal or plant taking to your county coordinator or to the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum.

Any Questions?

Please don’t hesitate to contact Allison Sacerdote-Velat or your county coordinator with any questions you have. Or pose your question to the Facebook Group, The Calling Frog Survey.

Thanks for your help in conducting this survey and have an enjoyable field season!

For specific information about the county you live in, contact the following county coordinators:

Cook County, IL

Forest Preserve District of Cook County: Mary Busch - 773-631-1790 x16 - Mary.Busch@cookcountyil.gov

Chicago Park District: Cassi Saari - cassi.saari@chicagoparkdistrict.com

DeKalb County, IL

DeKalb County Forest Preserves: Patrick McCrea - pmccrea@dekalbcounty.org

DuPage County, IL

Forest Preserve District of DuPage County: Cindy Hedges - 630-876-5929 - chedges@dupageforest.org

Kane County, IL

Forest Preserve District of Kane County: Robb Cleave - 630-762-2741 - CleaveRobb@kaneforest.com

St. Charles Park District: Patrick Bochenek - pbochenek@stcparks.org

Lake County, IL

Lake County Forest Preserve District: Norma Zamudio- nzamudio@lcfpd.org

Lake Forest Open Lands Association: Alex Barnes - abarnes@lfola.org

LASALLE County, IL

LaSalle County: Emily Hansen - emhansen@illinois.edu

McHenry County, IL

McHenry County Conservation District: Jackie Bero - jbero@mccdistrict.org

The Land Conservancy of McHenry County: Megan Oropeza - moropeza@conservemc.org

The Land Conservancy of McHenry County: Caroline Smith - csmith@conservemc.org

Will County, IL

Forest Preserve District of Will County: Julie Bozzo - JBozzo@fpdwc.org

Winnebago County, IL

Winnebago County Forest Preserve District: Keith Krey - KKrey@winnebagoforest.org

Rockford Park District/Severson Dells: Caedyn Wells - communityscience@seversondells.org

Other Illinois Regions

Please contact Allison regarding monitoring on other public lands not covered by the list above. Please note that some local Park Districts and Municipalities may take longer to receive approval from for monitoring permission/evening site access.

Northwest Indiana

The Indiana Dunes National Park routes are currently fully covered. Contact Allison and she will put you in touch with specific site contacts for IN Dunes State Park, Shirley Heinz Land Trust sites, and ACRES land trust sites as needed.

Each frog and toad species has a specific period in which chorusing and mating are most likely to occur. The timing of the breeding period is influenced by a combination of factors such as daily rainfall, soil, water, and air temperatures, and photoperiod. In northern Illinois, there are three distinct periods in which different species can be expected to breed. Monitors must conduct at least one survey for each of these periods. These periods, and the species that breed in them, are as follows:

- Early Spring February 25-April 20: In most years this period begins in the final two weeks of March and lasts until mid-April. Species which chorus during this period includes: boreal chorus frog, spring peeper, wood frog, northern leopard frog, and pickerel frog.

- Mid-Spring May 10-May 30: In most years this period begins in early May and lasts throughout that month. Species include: American toad, Fowler’s toad, eastern gray treefrog, and Cope’s gray treefrog.

- Late Spring/ Early Summer June 20-July 10: In northern Illinois, this period usually begins around the first week of June, lasting through July or early August. Species include: cricket frog, green frog, and bullfrog.

Some species — especially the American toad, boreal chorus frog, and northern leopard frog — occasionally chorus well after their normal breeding seasons are completed. This is most likely to happen during the cold weather of fall, or when cold summer weather systems stimulate early spring breeders.

The length of the breeding season varies from year to year and from species to species. The wood frog, for example, is an explosive early spring breeder. Wood frogs may begin chorusing at any time after the spring thaw, but all breeding activity is completed in two weeks or less (often just one to three days). Other species — such as the boreal chorus frog, American toad, and northern leopard frog — may chorus during all three breeding periods.

It is very important to be aware of weather conditions and be somewhat flexible when planning which nights to be in the field, especially during the early spring period. Volunteers may wish to sign up for The Calling Frog Survey Facebook group so that they can learn from other volunteers about the best nights to conduct surveys. Ideal weather conditions for most frogs and toads can best be described as seasonably warm, moist (light rain or foggy), with no more than light winds.

Need guidance on how to submit to PollardBase? Click here to jump to our instructional video.

To report additional visual or audio observations of frogs and toads that were not observed during your official survey route (e.g. daytime observations, phenological observations such as first calling heard during the season, calls heard outside of your survey area while traveling) we recommend the following databases below. Please note that these programs require either photos where distinguishing characteristics of species are readily visible, or recordings in order to validate your observations.

Chicagoland Frogs

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs were taken by Joe Cavataio and are used with permission.

Lithobates sylvaticus = Rana sylvatica

Markings: medium, brown/tan, dark eye mask

Call: chirdicks, chorus-raspy quack

The call of the wood frog is uncommon in the Illinois portions of the Chicago region. Record the calls of the species and contact your coordinator immediately if you think you have heard wood frogs in northeast Illinois. This species is difficult to find on a site due to its extremely short but explosive breeding period, sometimes only calling one or two nights a year. It breeds and calls in late winter or early spring, usually March in our area. The call of the wood frog consists of two rapidly emitted high-pitched chuckling notes. Up close, this call sounds like the frog saying "chirdick." From a distance, large choruses sound like the chattering of feeding ducks.

Pseudacris maculata (older field guides may show western chorus frogs, Pseudacris triseriata, for northern Illinois, but recent studies have revised the identity of our local species)

Markings: small, 3 stripes on back, black eye mask

Call: like finger over top of comb

Pseudacris crucifer

Markings: small, X on back

Call: high pitched “peep” chorus-sleigh bells

The spring peeper is uncommon but widely distributed throughout the region. It occurs in and around the larger forested tracks of the Chicago region. Although it is generally uncommon, some populations are still large. Locally, it may begin to call in March and often continues through May. This species call is a sharp bird-like peep. Two or three males chorusing closely together often sound like one frog saying "peeper." Large choruses heard from a distance may sound like distant sleigh bells.

Lithobates pipiens = Rana pipiens

Markings: medium, green with dark circular spots, white lateral folds unbroken

Call: soft course snore with chuckle

The northern leopard frog is fairly common, although it is seen more often than it is heard. The call is fairly soft and does not carry far, so check your site visually during the day for leopard frogs if your monitoring site contains old fields, or if you feel that you may not be hearing individuals on your visit. The northern leopard frog usually begins calling in early April and continues through early May. The call of the northern leopard frog can consist of two sounds. The first sound is a coarse snore, like a finger being rubbed over a dry inflated balloon. The second is a series of coarse or raspy sounding chuckles.

Lithobates blairi = Rana blairi

Markings: green with dark spots circular spots, white lateral folds broken near groin

Call: low chirks & snores

The plains leopard frog is rare in the Chicago wilderness region and should only be seriously considered as a possibility if you are monitoring in the southwestern extreme of the region in Will County. Record the calls of this species and contact your coordinator immediately if you think you have heard plains leopard frogs. They call in April and May. The call of the plains leopard frog is a series of three or more pulsed or definitive chuckles, usually repeated two or three times in rapid succession. The pulsing chuckles sound as though the frog is saying "chirk-chirk-chirk." This species also emits calls which sound like low snores.

Lithobates palustris = Rana palustris

Markings: cream with square spots

Call: ticking snore “yeow”

The pickerel frog is extremely rare in the Chicago region. This frog will only occur in areas with high amounts of surface groundwater such as fens, small spring-fed streams, and seeps and may be completely extirpated from this area. Record the calls of the species and contact your coordinator immediately if you think you have heard pickerel frogs. They call in April and May. The call of the pickerel frog is best described as a rapid or ticking snore. It has a slightly rising inflection, almost as if the frog is saying "meow" or "yeow" as it snores.

Picture by Lalainya Goldsberry

Anaxyrus americanus = Bufo americanus

Markings: 1-2 warts per spot; large gland behind eye, unattached to bony crest, unless by a short spur

Call: 10-30 second melodious trill

The American toad is common throughout most of the Chicago area. Not only is this toad found in many of our natural areas, but it can also often be heard in some of Chicago's urban neighborhoods. This species begins calling in early April and continues through May and sometimes beyond. The call of the American toad consists of a long and pleasing musical trill. This is the longest continuous call of any Chicago area frog or toad and, depending on the individual, it may last from several seconds to almost 30 seconds. It is very common for the calls of just a few individuals to overlap.

Hyla/Dryophytes versicolor | Hyla/Dryophytes chrysoscelis

Markings: lichen pattern (gray or green), light patch below eye, yellow inner thighs

Call: Eastern: musical trill; Cope’s: fast harsh trill

The call of the eastern gray treefrog is often described as a melodious or musical trill. Under similar air temperatures, the call of the eastern grey treefrog sounds much more musical and slower than the fast trill of Cope's gray treefrog. The Cope's gray treefrog call is generally more harsh in quality.

Pictured: Cope's gray treefrog

Anaxyrus fowleri = Bufo fowleri

Markings: 3 or more warts in large spot, large gland touches bony crest, sand habitat

Call: distressed sheep

Fowler's toad is uncommon in the Chicago region. It is restricted to areas of sandy soil, usually close to Lake Michigan. If you are not on the Lake Michigan shoreline or Kankakee Sands area, do not expect to hear this frog. It is still locally common in the dunes area in northwest Indiana. However, frog monitors hearing the Fowler's toad elsewhere in the Chicago wilderness region should immediately contact their coordinator. The coordinator can arrange for another monitor to confirm the record. It is always desirable to have multiple confirmations of rare species. The Fowler's toad calls in May and June. Its call is best described as a nasal bleat or cry. It is sometimes described as similar to a bleating or distressed sheep.

Acris crepitans

Markings: small, triangle patch between eyes, warts

Call: clanking marbles

The cricket frog is a species that has declined in the heavily urbanized parts of the Chicago region. Recent confirmed reports come from Kane and Will counties. Contact your county coordinator immediately if you hear or observe this species so your observation can be confirmed. The cricket frog breeds in late spring and early summer. It gets its common name from its insect-like mating call. This call is best described as a series of clicks which sound like two marbles being struck together, increasing in frequency and then abruptly slowing again towards the end of the call.

Lithobates clamitans = Rana clamitans

Markings: large, green to brown, lateral folds 2/3 of body

Call: banjo “gung”

The green frog is fairly common in weedy ponds, streams, rivers, and other water bodies throughout the Chicago region. It is a late spring or early summer breeder and calls in May and June. The mating call of the green frog is often described as sounding like the twang of a loose banjo string. Several calls may be described as sounding like a fast series of gulps.

Lithobates catesbeianus = Rana catesbeiana

Markings: large, green to brown, lateral fold to ear

Call: deep “br-wum”

The American bullfrog is the largest frog in the Chicago region. These impressive creatures occupy just about any permanent body of water throughout the region. The bullfrog is a late spring or early summer breeder and calls in May and June. The mating call of the bullfrog is best described as a low rolling roar or a bow being drawn across a string bass and is repeated two or three times.

Training Videos & Additional Video Resources

Test Your Skills

Embedded below is a browser-adapted version of a touchscreen game developed for our exhibit By A Thread: Nature's Resilience. The prompts and instructions are for participants playing on a touchscreen device, so please make adjustments as needed if you are running the game on a computer. Due to the way it is embedded, it will not resize properly on a mobile device unless it's opened in a separate window.

Please note, the game may take time to load fully. If you'd prefer to try it in a separate browser window, please click here.

Survey Results

Monitors have found all thirteen species known to occur in our region. Below is a summary of who has been found from the most common species to the least. Based on abundance, the frogs and toads fell roughly into three groups:

Group 1 - Chorus frog, green frog, American toad, and bullfrog were commonly discovered at most locations.

Group 2 - Spring peeper, Cope’s and eastern gray treefrog, and northern leopard frog were less common but locally abundant during certain years.

Group 3 - Cricket frog, wood frog, Fowler's toad, plains leopard frog, and the pickerel frog were generally quite rare and local.

Numbers and species of frogs/toads recorded are highly dependent on temperature, weather and terrain, so their relative abundance varied from place to place and from year to year.

The Calling Frog Survey: A trend analysis of the proportion of sites occupied by our regional frog species from 2004-2021

Overview

Monitors have found all thirteen species known to occur in the Chicago Wilderness region. However, some species are far more widespread, while others have greater habitat specificity that limits their distribution. For example, Plains leopard frogs are found in some of the sand prairie habitats in the region. If you do not have this habitat type along your route, you would not expect to find the species there.

Using 18 years of community science data from our frog monitors, we have examined trends in the proportion of sites occupied by each species between 2004 and 2021. For this analysis, we included 79 survey routes that had at least four seasons worth of data. If you have only recently joined the network, we hope you will continue monitoring so we can incorporate your site into additional long-term analyses. We used four years of data as a minimum because annual conditions such as droughts, late springs, and flooding can influence which species will use a site for breeding in a given individual season. Four years also allows for some variation in environmental conditions and is reflective of the reproductive generation time for the larger-bodied frogs, while some of the smaller frogs may reach reproductive maturity within a single year.

For each species, we use the frog monitors’ data to create an encounter history for each site. Each species has a different likelihood of being detected by monitors based on the survey window, air temperature, and wind speed. So while some species are very audible, like boreal chorus frogs and spring peepers, other species are more likely to be missed, like northern leopard frogs and wood frogs which call underwater. Because each species of frog has “imperfect detection”, we create models of the proportion of sites occupied, which accounts for the likelihood of a particular species being heard or detected during each survey window.

Species Trends

Common Species

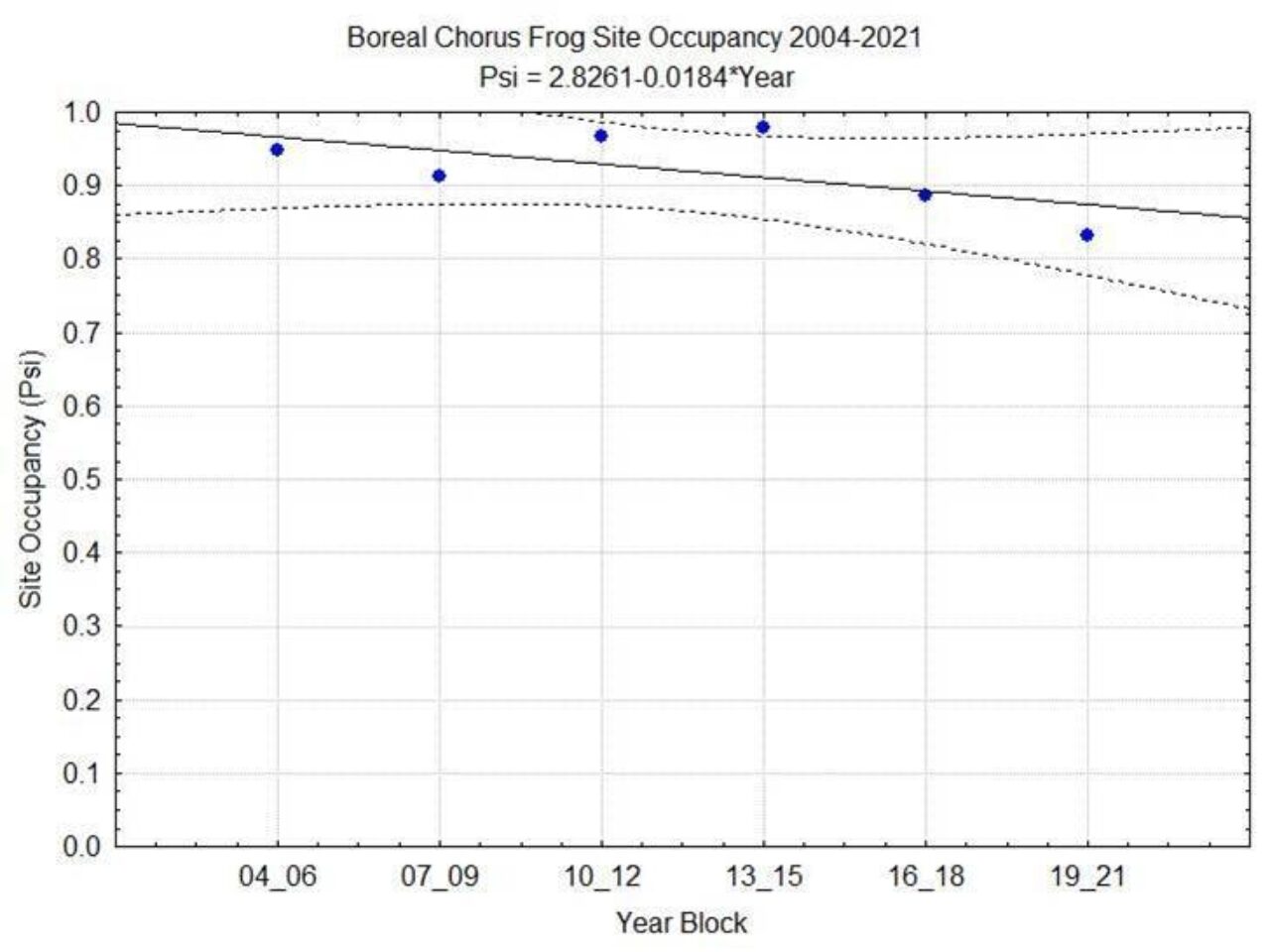

The most widespread species in the entire survey area, spanning 10 counties in the Chicago Wilderness region, was the boreal chorus frog. Site occupancy for the boreal chorus frog did not show any significant change over the 2004-2021 time window (Fig. 1). The proportion of occupied sites was consistently greater than 80% (or 0.8 in the figure below). The slight decrease visible in the 2019-2021 year block reflects that a smaller number of sites were able to be sampled in 2020 during the first monitoring round, because of COVID-19 lock down. Additionally, the severe drought in 2021 dried many breeding ponds very early in the season.

Figure 1. Proportion of sites occupied by boreal chorus frogs between 2004 and 2021 based on encounter histories from 79 survey routes. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

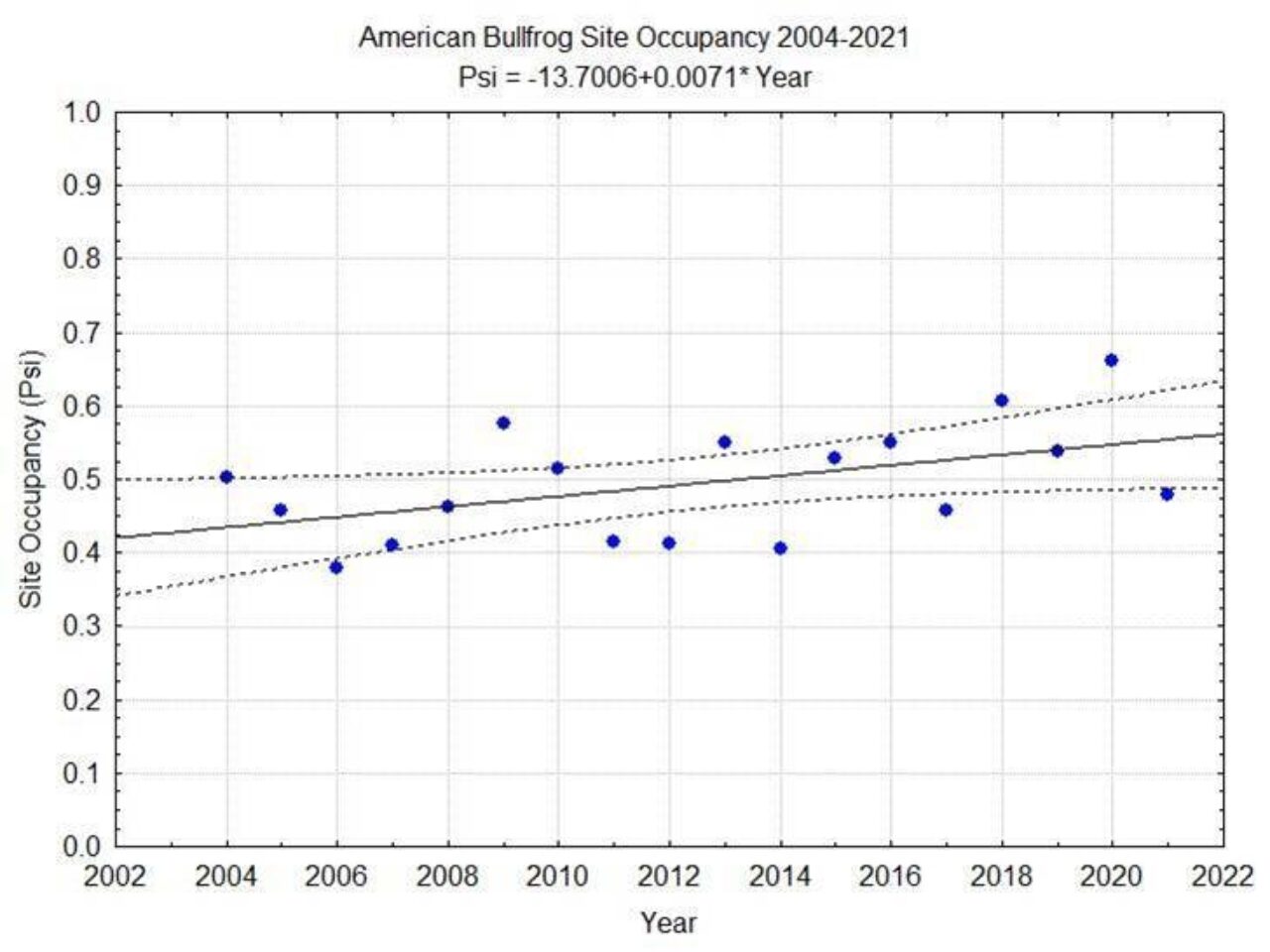

We found that American bullfrog and green frog site occupancy has been significantly increasing in the region over the last 18 years. American bullfrogs were generally found on 40-60% of surveyed sites (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Site occupancy of American bullfrogs between 2004-2021 based on encounter histories from 79 survey routes. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

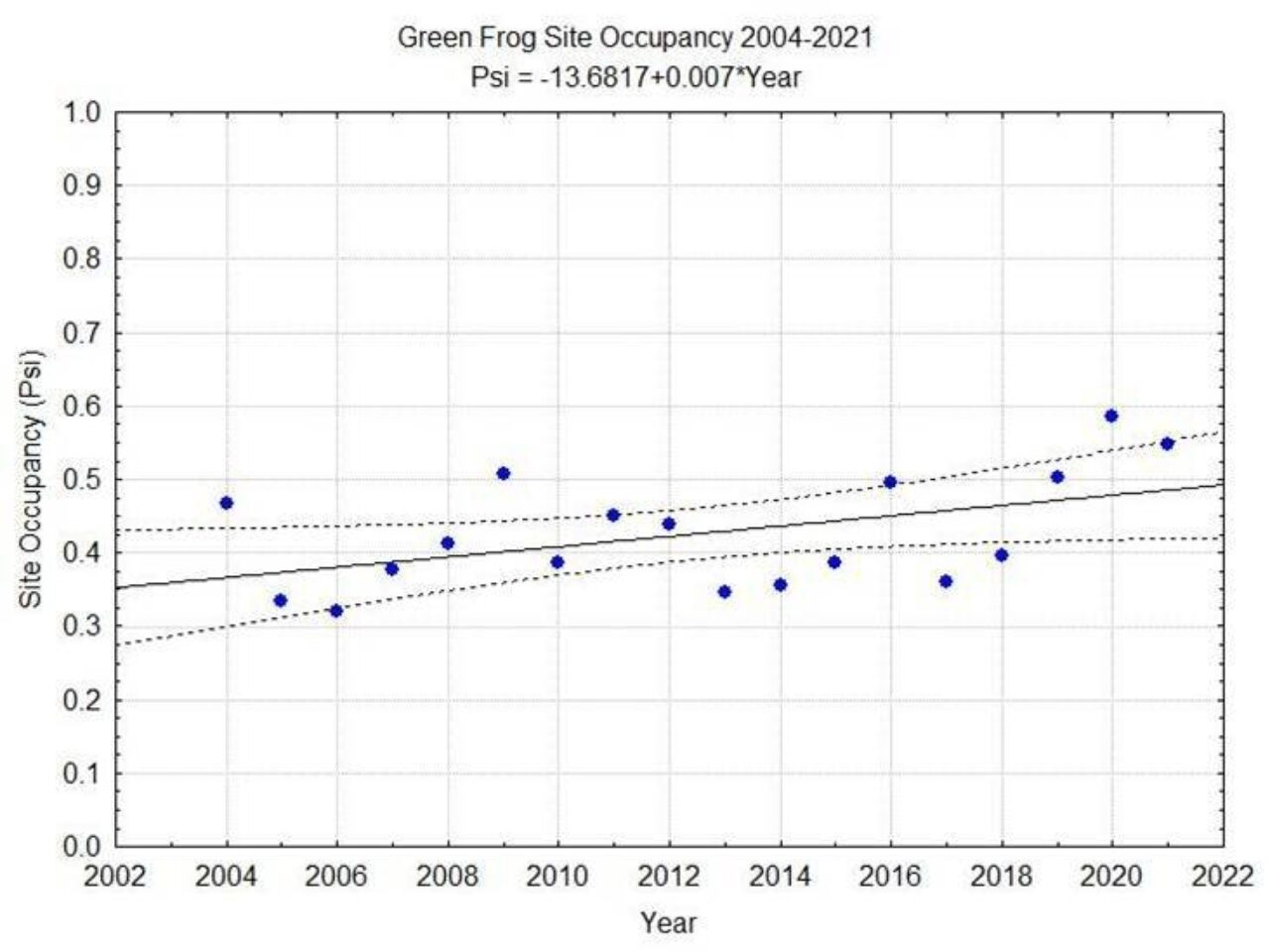

Green frogs have also shown a significantly increasing trend in site occupancy, although they have been found on a smaller proportion of sites than American bullfrogs (Fig. 3). Green frog site occupancy has remained between 30-50% of sites in the last 18 years.

Figure 3. Site occupancy of green frogs between 2004-2021 based on encounter histories from 79 survey routes. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

Both American bullfrogs and green frogs breed in permanent bodies of water, typically with dense vegetation such as duckweed. The tadpoles of both species may overwinter for multiple seasons, and may co-occur in sites with fish. Because of their use of permanent water bodies and because of their large body size, bullfrogs and green frogs can make use of many artificial or highly modified water bodies such as detention basins, golf course ponds, and lagoons in city parks. Their larger body size enables greater dispersal between sites, so they are more likely to colonize new breeding sites than many of the smaller frog species in the region.

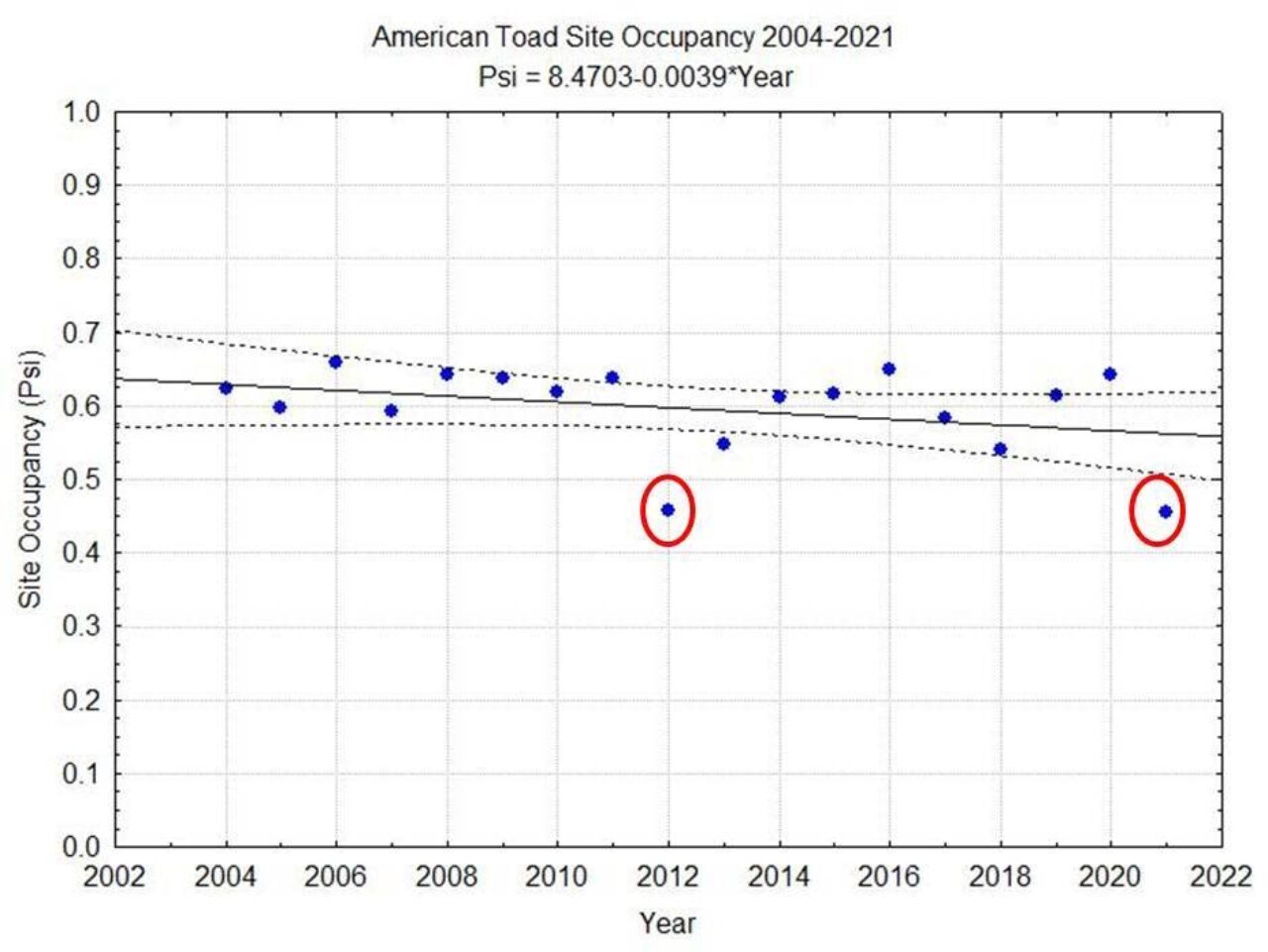

American toads, the most terrestrial of our regional frogs, occurs in about 55-65% of the routes in the region. While we are observing a slight downward trend in American toad site occupancy, it is not a significant decline in occupancy across years (Fig. 4). We observed noticeably lower site occupancy for American toads in 2012 and 2021 (circled in red in the figure), the two most severe droughts in the region in the 18 years included in the analysis. Because American toads breed beginning at the end of Round 1 into Round 2, their phenology coincides with the point in each of the drought years when most of the breeding ponds were drying up.

Figure 4. Site occupancy of American toads between 2004-2021 based on encounter histories from 79 survey routes. The red circles indicate severe drought years when ponds dried during the typical window for peak calling activity for American toads. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

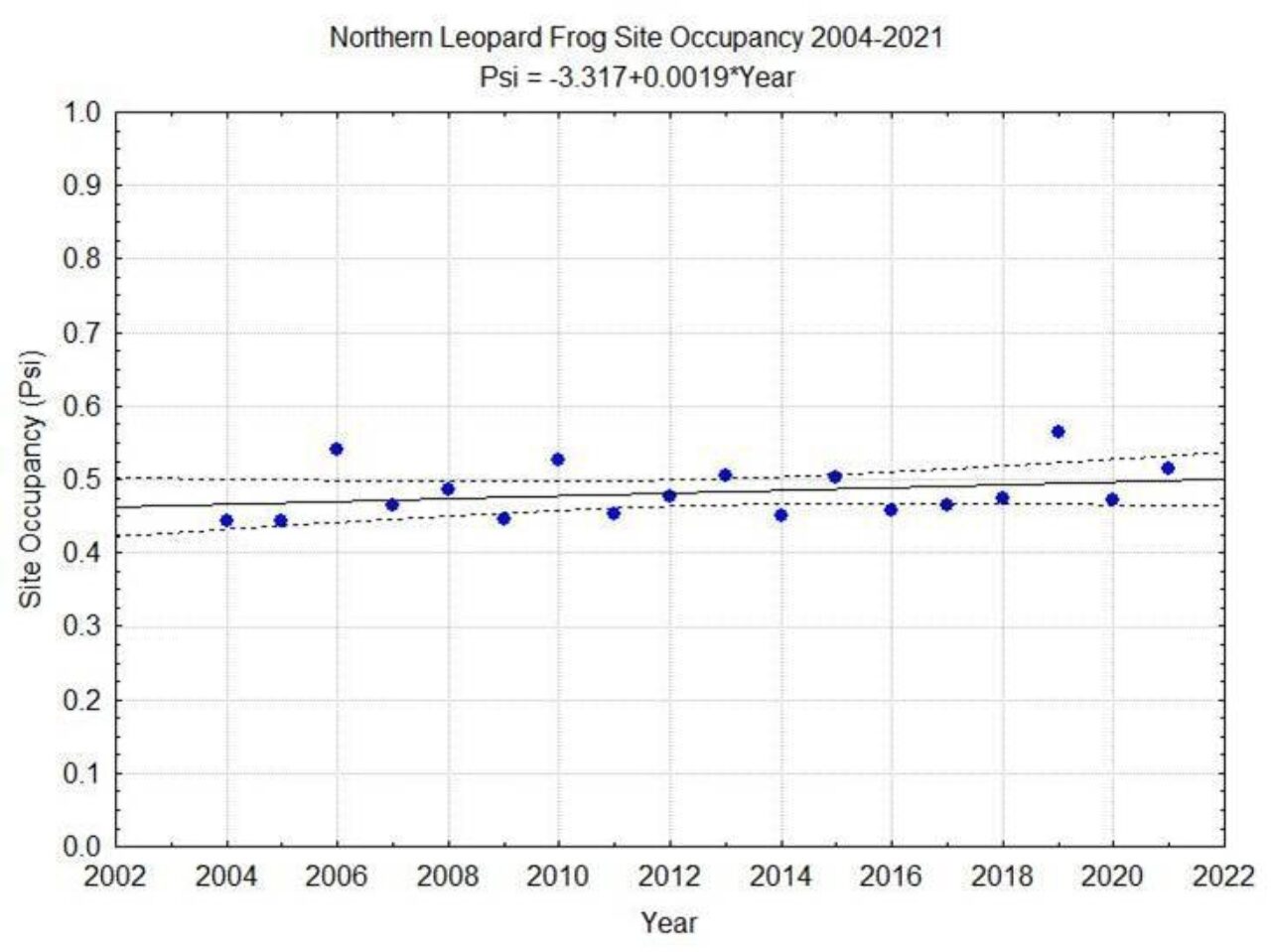

Northern leopard frogs did not exhibit a significant trend in site occupancy between 2004 and 2021. They were found on 45-55% of the survey routes in the region (Fig.5). Detection rates for northern leopard frogs are generally lower than some of the other large pond frogs because they inflate their vocal sacs underwater when calling, so the call is naturally muffled to our ears. Additionally, because their calling activity occurs during Round 1 (typically late March/early April) their calls are often masked by the louder calls of the boreal chorus frog and spring peeper. If you want to ensure that you can detect the northern leopard frog call, we recommend recording the calls you hear on your route and then playing them back at home. Many digital media players on computers allow you to adjust the treble and bass settings so you can reduce the high frequency calls and boost audibility of the low frequency calls. Similarly, we are happy to run any recordings through spectrogram software to visually pick out the masked calls.

Figure 5. Site occupancy of northern leopard frogs between 2004-2021 based on encounter histories from 79 survey routes. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

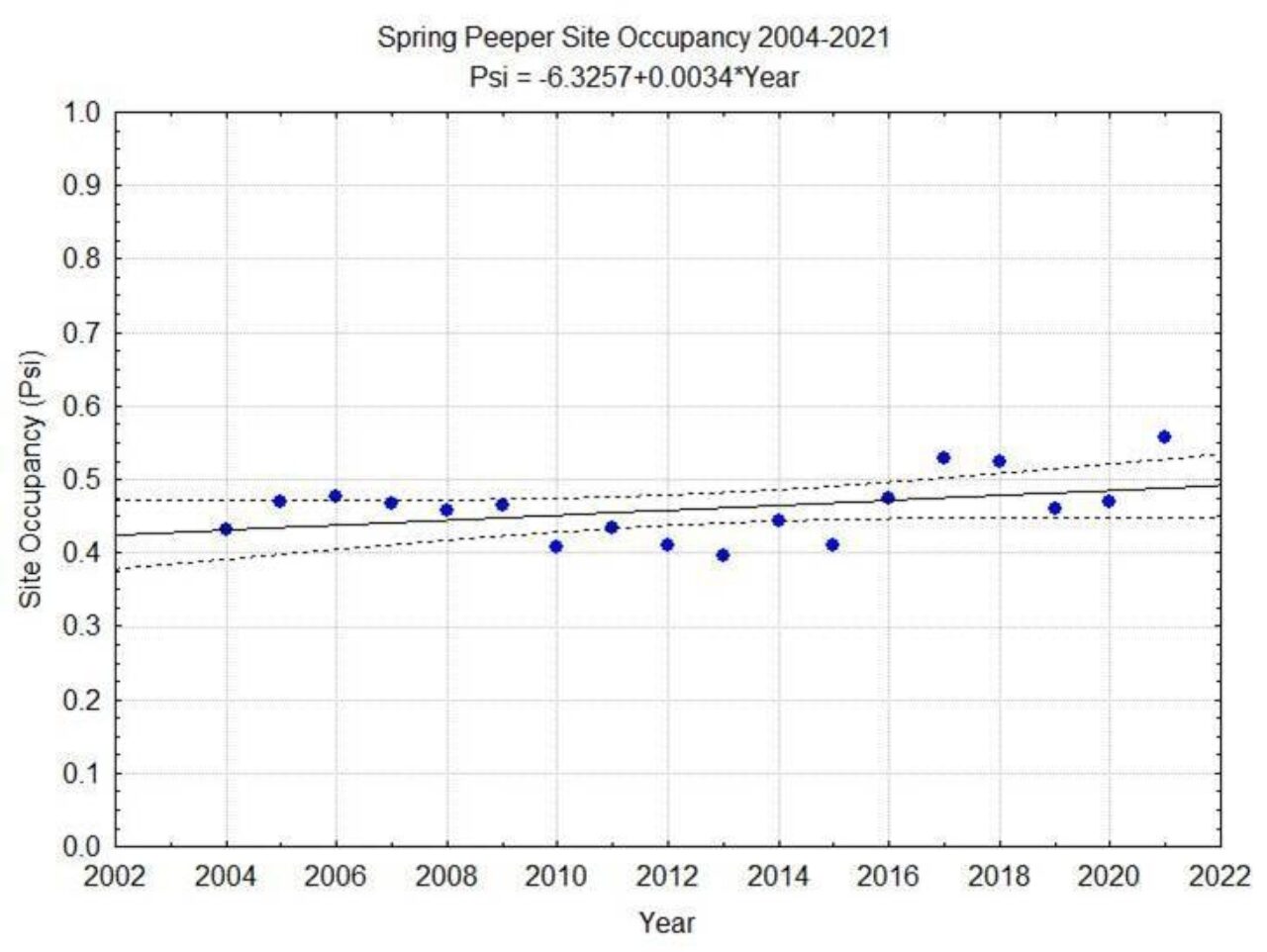

Spring peepers, one of the most readily detectable species in the survey area, did not exhibit a significant trend in site occupancy over the last 18 years (Fig. 6). While we are aware of localized declines from a few sites, we also had a few colonization events where monitors detected spring peepers in recent years after several seasons with no evidence of their activity in particular sites. Overall, spring peepers occupied between 39-57% of our survey routes between 2004 and 2021.

Figure 6. Site occupancy of spring peepers between 2004-2021 based on encounter histories from 79 survey routes. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

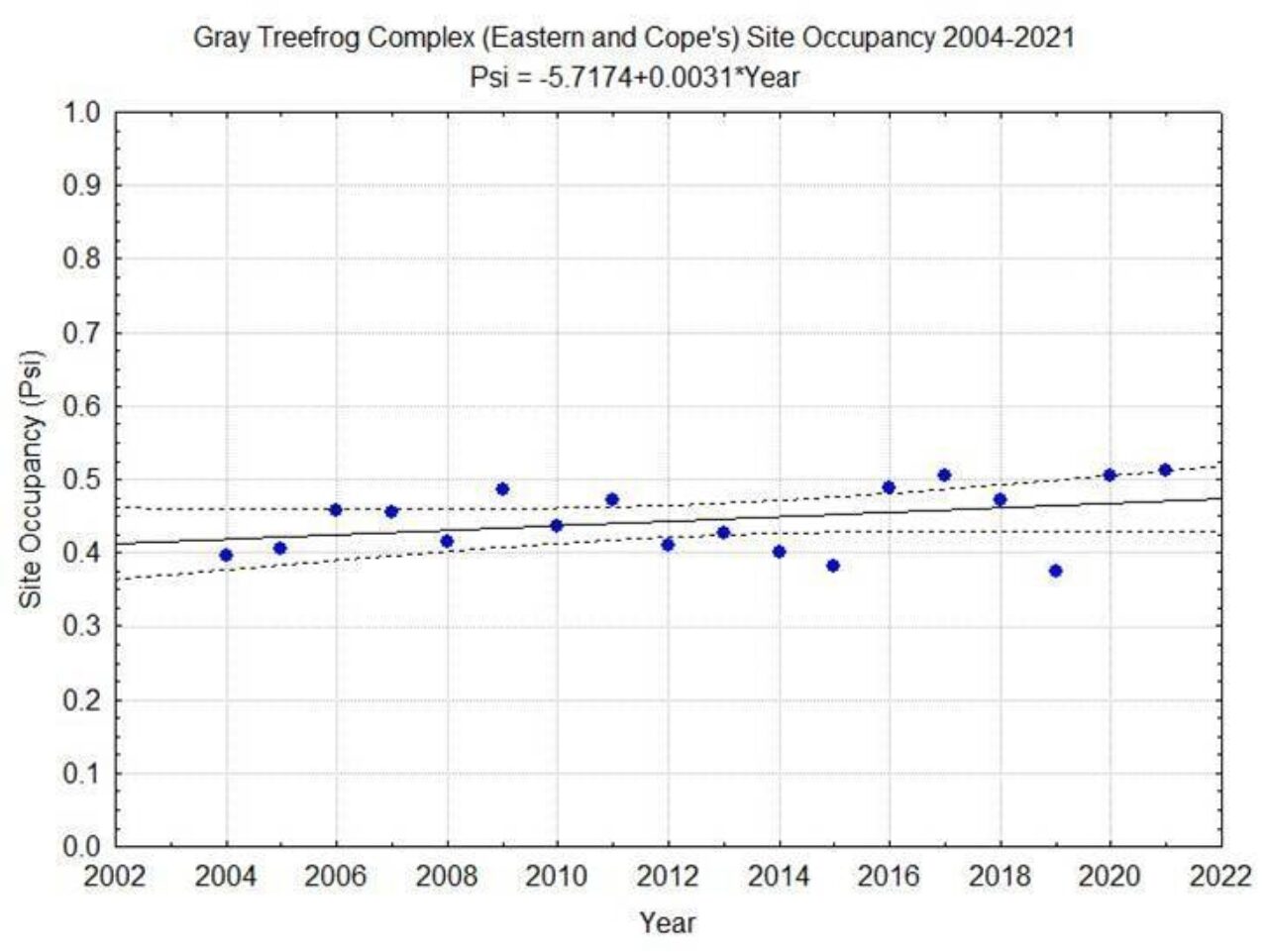

For the purposes of these long-term analyses, we combined the two species of gray-treefrogs into one gray-treefrog complex as we lack verification of which gray treefrog was detected for some of the early years of the program. We did not observe a significant long-term trend in gray treefrog site occupancy. The site occupancy for gray treefrogs ranged from 38-50% of survey routes (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Site occupancy of gray treefrogs (combined eastern and Cope’s) between 2004-2021 based on encounter histories from 79 survey routes. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

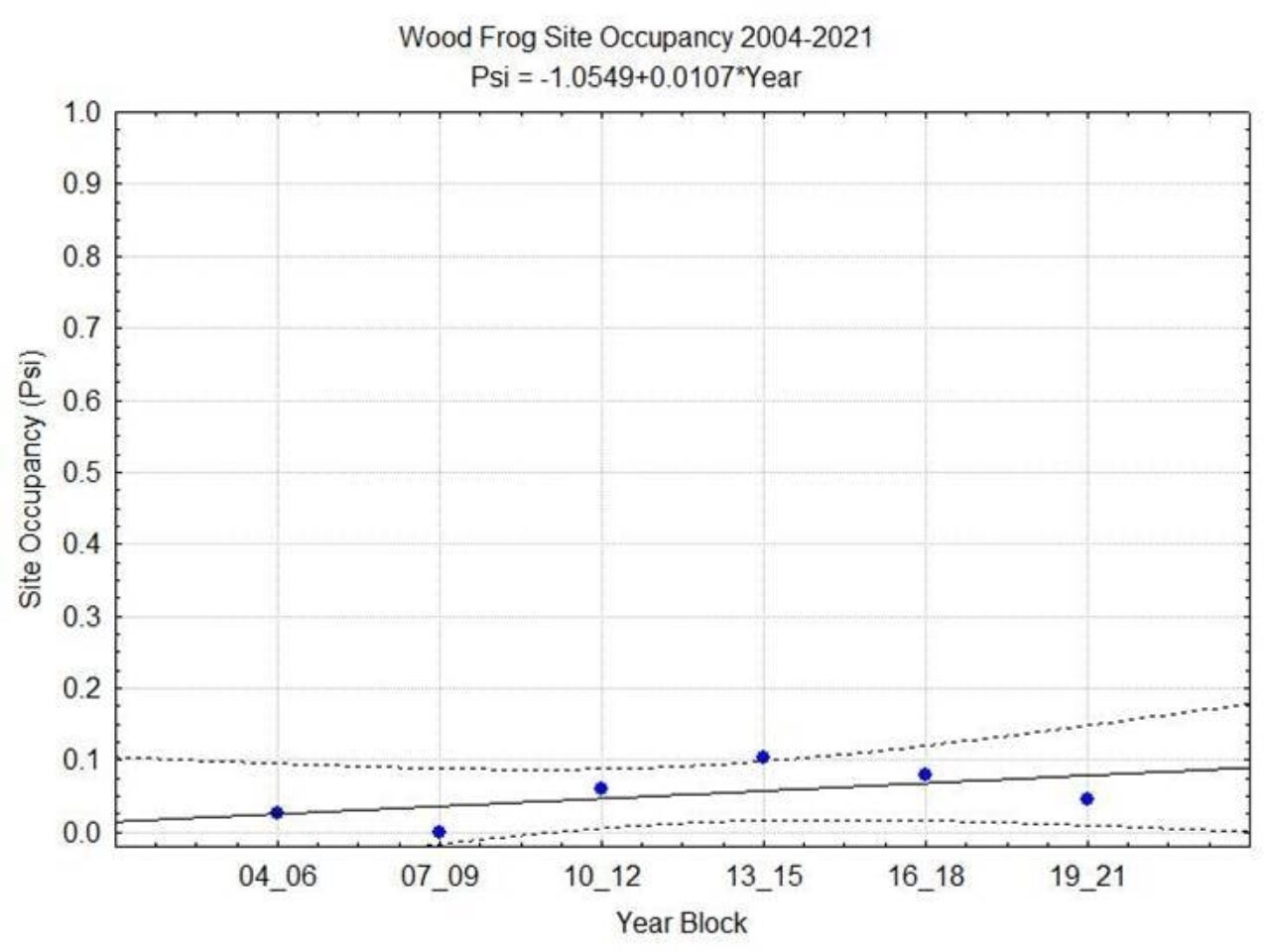

Wood frogs, one of the early, explosive breeders, are highly isolated in their geographic distribution in the Chicago Wilderness region with their stronghold in northwestern Indiana’s dune swale ponds and flatwoods. We did not find a significant trend in their site occupancy between 2004-2021, but we were also data deficient for a few of the known-occupied sites for several of the years included in the analysis. We collapsed observations into six 3-year blocks and examined site occupancy across the six time windows. In most years, wood frogs occupied less than 5% of the survey routes. Wood frogs are a challenging species for monitors to detect because of their explosive breeding behavior. They may call for a single night or for about a week and a half. While they may be found calling when ice is present on the ponds, in our survey data, monitors typically detect them after the boreal chorus frogs have started calling, rather than in advance of them. In most occupied sites, the chorus frogs and spring peepers are overlapping the wood frogs, so call masking is a possibility. However, the wood frogs are typically completing their calling during the last week of March or first week of April. Another challenge is distinguishing the territorial “chuck” sound of the northern leopard frog from the breeding call of the wood frog. Because of the similarity in the sounds, it is important to (1) record the calls and have them verified by the Calling Frog Survey director, (2) pay close attention to the phenology—if you are hearing a chuck in late mid to late April, it is much more likely to be a northern leopard frog than a wood frog. Both species inflate their vocal pouches underwater, so the sound is muffled for both calls, but they have distinct frequencies that we can examine using spectrograms to distinguish the identity of the species.

Figure 8. Site occupancy of wood frogs between 2004-2021 based on encounter histories from 79 survey routes. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

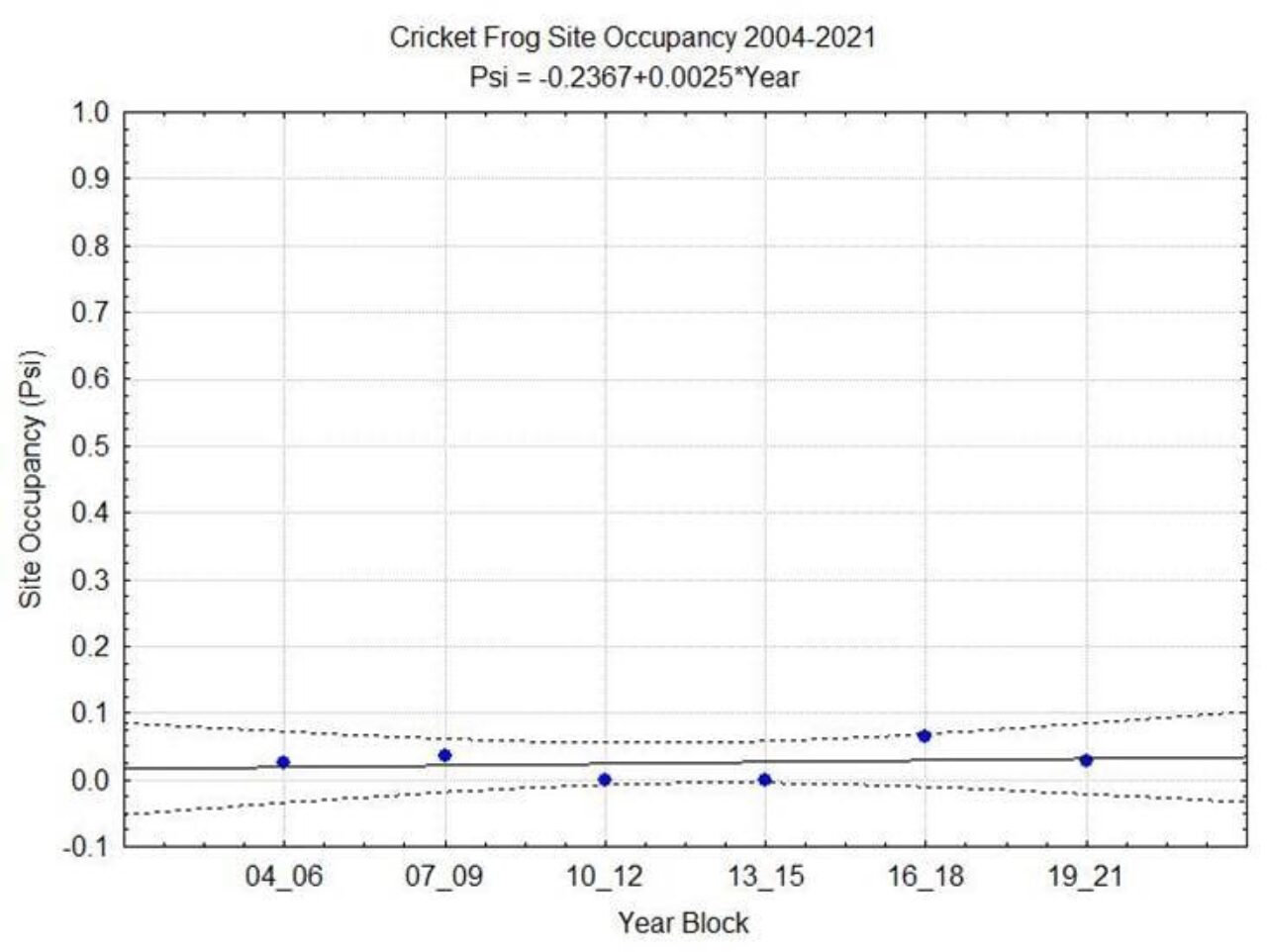

The cricket frog is one of the rarest species in the region, occupying less than 5% of the survey routes. This was once a widespread species across northern Illinois counties, but recent studies have found enigmatic declines which may be associated with a number of drivers including habitat fragmentation and disease. In the sites where we do have cricket frogs, they are locally abundant and we are aware of a few colonization events in southern DuPage County and in DeKalb County. Many of the DeKalb county sites are newer additions to the monitoring program with less than four years of data, so they were not included in this long-term trend analysis. This analysis reflects cricket frog site occupancy with observations restricted to Will County and southern DuPage County.

Figure 9. Site occupancy of cricket frogs between 2004-2021 based on encounter histories from 79 survey routes. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

For the remaining rare species; the plains leopard frog, the Fowler’s toad, and the pickerel frog, we have only isolated observations from individual sites and we lack sufficient long-term data from these sites to conduct a trend analysis. If you think you are hearing the call of any of these three species, we need recordings in order to verify presence of these species. All three species have some habitat specificity to sand prairie for the plains leopard, dune/swale/interdunal ponds for the Fowler’s toad, and cold groundwater-fed springs and fens for the pickerel frog. Because of shoreline development, limitation of the extent of sand prairies, and regional hydrologic alteration, these species will be limited in distribution, but we would love to collect any data that we can from isolated sites where they may persist.

Contact Us

Questions about the program? Looking for additional resources? Use the form below to get in touch with our team.